USATF 5K Championships 2014Sep 18, 2014 by Joe Battaglia

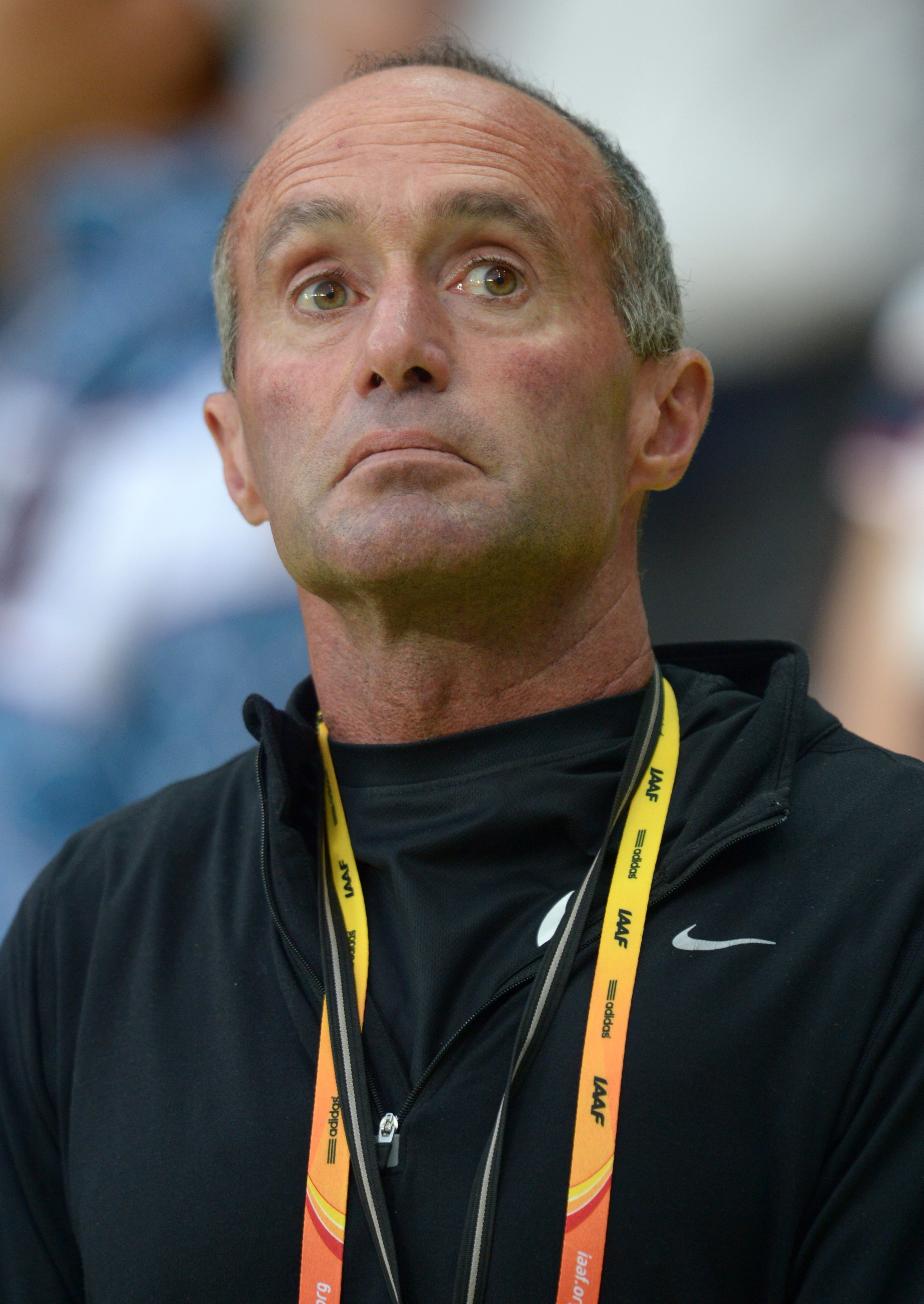

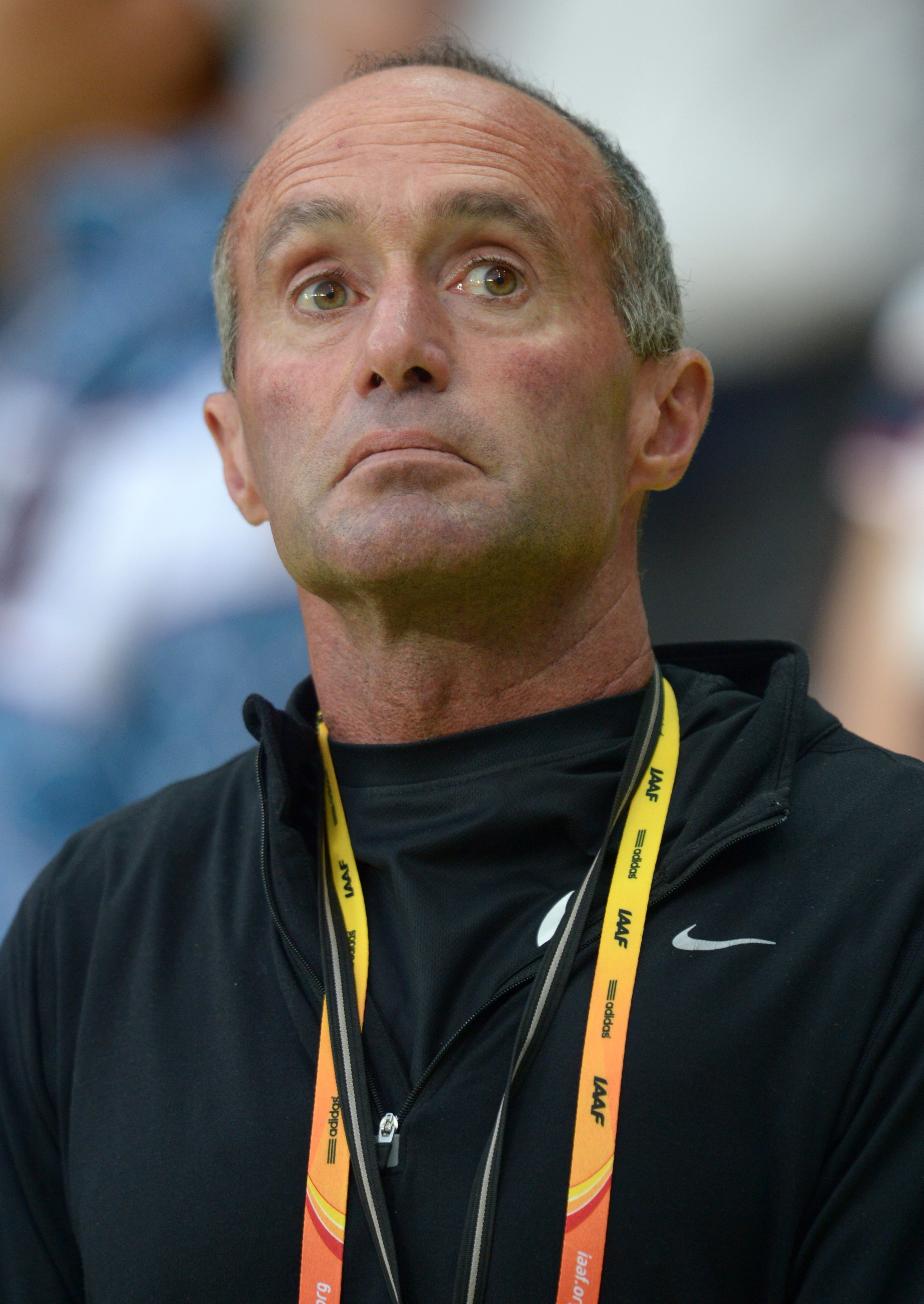

Mary Cain Found Her Calling With Alberto Salazar

Mary Cain Found Her Calling With Alberto Salazar

NEW YORK -- The clock was still far from ushering in the bewitching hour one early-October evening two years ago when the phone rang in the Cain household tucked in an affluent village in Westchester County.

Mary, a precocious middle-distance running talent for the local high school in Bronxville, was already tucked in bed at the time.

The caller ID registered an unrecognizable Oregon number. Fully anticipating it to be one of those annoying telemarketers, the call went unanswered and straight to the answering machine.

The voice on the other end of the line introduced himself.

“Hello, this is Alberto Salazar.”

Now two years removed from that fateful night and into an “amazing partnership,” that has already seen her reach the final of the 1500m in her first trip to the World Championships and win gold in the 3000m at the World Junior Championships, Cain wonders where she would be today had Salazar not reached out.

“It’s crazy looking back,” Cain admitted during a conversation in the lobby of the venerable 89th Street office of the New York Road Runners. “That week I was actually debating whether or not I should take a two-year leave of absence from the sport. There was also ambitious goal setting from the outset.

There was also ambitious goal setting from the outset.

“Then came a phone call which started off with Alberto being like, ‘I just want to give you some advice,’ to one that has turned me into a professional athlete living in Portland.”

TRIALS RUN IN

Cain actually had her first meeting with Salazar, now the esteemed coach of the Nike Oregon Project, earlier that summer at the 2012 U.S. Olympic Trials – as a wide-eyed, 15-year-old fan of the Cuban immigrant from Massachusetts who won three consecutive New York City Marathon titles from 190-82 and won the famed “Duel in the Sun” over Dick Beardsley at the 1982 Boston Marathon.

“I took a picture with him because he is Alberto Salazar,” Cain said. “It was actually pretty funny because I was so nervous going over to him and he was like, ‘Oh, are you that fast high school girl?’ And I was like ‘Yeah!’”

Salazar’s recollection of the moment is more matter-of-fact.

“She and her coach came by and the coach introduced us,” he said. “I had heard of her before and so we just chatted a little while.”

Added Cain: “Since then, I’ve asked him, ‘How did you know who I was?’ He goes, ‘You know, being an East Coast guy I always loved it when East Coast people would beat those California kids so you were kind of on my radar.’”

The two went their separate ways after that meeting, Salazar on to the London Olympics where he guided Britain’s Mo Farah to gold medals in the 5000m and 10,000m and American Galen Rupp to silver in the 10,000m, and Cain off to the World Junior Championships in Barcelona where she finished sixth in 4:11.01, breaking the American high school record.

The two went their separate ways after that meeting, Salazar on to the London Olympics where he guided Britain’s Mo Farah to gold medals in the 5000m and 10,000m and American Galen Rupp to silver in the 10,000m, and Cain off to the World Junior Championships in Barcelona where she finished sixth in 4:11.01, breaking the American high school record.

When Salazar returned home from the Games, he pulled up a YouTube video of Cain’s race and was struck as much by her raw speed as her biomechanics, which featured a fluid stride but a chicken-wing arm swing – Cain says her arm motion was “absolutely awful” – due to lack of upper-body strength.

“I remember kind of seeing her form and how she was really running with her elbows out and stuff,” Salazar said, “so I called her coach to tell him to make sure that he worked on her form and that she could have a great career if they worked on her biomechanics. The coach that I was put through told me that he was no longer coaching her. I asked, ‘Well who is coaching her?’ He said we don’t know yet.”

So Salazar asked for Cain’s phone number.

CALLING PLACED ON HOLD

Cain returned home from Europe for the start of her junior year at Bronxville High, but while her peers were readying for the start of the cross-country season, she was a runner without a home.

She had parted ways with her high school coach, a situation she chooses not to delve into specifically, only saying that it “was not healthy and it had nothing to do with me or my family; it was just other outside influences that were making it difficult for me to continue.”

While Cain never lost her passion for running – “I told my parents, ‘I can’t not run. I have to. I can’t just leave it,’ she said – she was lost navigating the world of running. Without a coach directing her course, she wrote her own workouts but was clueless as to how or where she could race.

“I wouldn’t have known where to go on the local circuit,” Cain said. “I don’t even know what that means. I had absolutely no guidance. I was out there training myself, doing my own thing. I wanted to do local stuff but we didn’t know what to do. We were at a loss.”

The predicament seemed so hopeless that Cain gave serious consideration to giving up running for the remainder of her high school years.

“My parents and I were literally contemplating calling up college coaches, calling Oregon, Georgetown, Stanford, all of those places and saying, ‘Hey, I am going to stop running for two years,’” Cain admitted. “We were at the point of telling coaches, ‘I’ve run 4:11. I know I can run better. I can’t do it right now, but remember me in two years!’”

Salazar says that had Cain been forced to make that decision, she might not have been able to fully reach her potential.

“If she had decided to not run at all and then try to start again in college, it would have obviously been a huge step backward for her,” he explained. “She would have lost all of that conditioning and momentum she had going forward. Not that it would have been impossible to start up again but taking a two-year break is pretty tough.”

For her part, Cain isn’t sure what would have happened.

“Honestly there is a very good chance that Mary Cain wouldn’t have run at all her junior or senior years of high school,” she said. “I’d like to think that the college coaches would have called me two years later. There might be some excitement this weekend to see what I would be doing in cross country because you wouldn’t have seen me since that day I ran 4:11.”

THE RIGHT CALL

Desperate times call for desperate measures. Cain thought back to that day she met a running icon and got her picture taken with him at the Trials. Call it a dream or a prayer, but she wondered if Salazar would ever consider coaching someone like her.

“I joke with Alberto that at the time I was actually looking for his email to reach out and say, ‘Hey, I know you’re super-cool and I’m just a random kid, but if you could even just give me some advice, I would be forever grateful,’” Cain said. “I literally told my mom the week before that I was going to do that. I said, ‘He seems like such a nice guy. I’m sure he would at least email me back.’

“I joke with Alberto that at the time I was actually looking for his email to reach out and say, ‘Hey, I know you’re super-cool and I’m just a random kid, but if you could even just give me some advice, I would be forever grateful,’” Cain said. “I literally told my mom the week before that I was going to do that. I said, ‘He seems like such a nice guy. I’m sure he would at least email me back.’

“And then he called me.”

Upon hearing the name “Alberto Salazar,” come through the answering machine, Cain’s mother, also named Mary, leapt to her feet and dove for the phone like she was lunging across an Olympic finish line.

“I did the 100-yard dash in two seconds,” she told espnW last April.

“The only thing I heard was my mom bolt for the phone,” Cain said, adding that the noise startled her for a moment, but did not fully wake her.

“I ended up calling (Cain’s) parents and said whoever is coaching her, or if you can find some club coach, have them work on her mechanics,” Salazar said. “Her mom asked me if I knew of any coaches out there and I said that I didn’t really know but that she could ask around and maybe there were some club coaches.

“She asked if I would be willing to give her some workouts at least temporarily to get her through the cross-country season, and I said ‘Okay, yeah. Fine. I can do that.’”

Two hours later, Cain was woken by her parents and let in on the conversation.

“When he actually called, I can’t tell you the level of excitement,” Cain’s father, Charlie, told The New York Times in 2012. “Mary was very excited. It was quite literally an answer to a prayer.”

“My mom still jokes about this, but when we got the call from Alberto she was the most excited because she was like, ‘I watched your marathons! I know who you are!’” Cain said. “And of course we watched the London Olympics. I was actually at the beach when the 10-K was going off. Nobody else in my family runs besides me, and they were all there sitting and watching it. I come home five minutes later and was like, ‘You didn’t call me?’ So I had to watch it myself online.”

A few days after Salazar’s initial phone call, Cain spoke to him on the phone and the two “just really clicked pretty instantly.”

"The first time we sat down he said, 'This is a 10-year program. I don't want you peaking at age 16,'" Cain told espnW last year.

Salazar added: "Mary knows what I told her; she has as much talent as any young athlete I've ever seen in running -- in my life."

After those initially conversations, Cain began getting direction from Salazar. It didn’t take long for word to spread that the two were working together.

“When everybody found out about it, it was probably two or three weeks after we had first met,” Cain said. “There were a lot of people saying, ‘Oh, you were meeting secretly in the summer.’ That was all me coaching myself. I was doing my little random workouts there. They were pretty good. I was proud of those. But finally he was like, ‘Okay, we’re going to start giving you workouts and building up to it.’”

When the Cains realized they had found the perfect coach for their daughter, they proceeded quickly, but not star-struck.

“We were all big fans of Alberto, but the big thing with my parents was that they wanted to make sure that it worked,” she said. “They didn’t want me to get into a super-intense program that is crazy that early. Alberto is the best coach in the world. When we sat down and talked to him, we also realized that he is the nicest guy in the world, and is really there for his athletes. He pours 110 percent into each of us. It was like, how could I say no? We had no real reservations.”

STARTING SLOWLY

Salazar, however, did give pause.

“I started telling her a few workouts to do and she did pretty well,” he said. “We kept talking a couple of times a week, and they asked me if I was willing to continue doing that. I had to think about that carefully. Just the responsibility of getting involved with a 16- or 17-year-old girl living across the country, and whether I had the time to put forth the commitment to do it. But then I said, ‘What the heck.’ It had gone pretty well for the first month so why not.”

Because Cain did not want to move to a boarding school in Oregon, Salazar needed to find a coach-in-residence, so to speak. He enlisted the help of John Henwood, a 2004 Olympian for New Zealand who works as a coach and massage therapist in Manhattan, to supervise her daily workouts.

“John Henwood has done a fantastic job,” Salazar said. “I feel like Mary has been well-monitored while she’s here.”

“Alberto and I sat down in person when he was in town for an appearance,” Cain recalled. “He said his goal was for me to make the 2013 Worlds team and I actually kind of laughed in his face. I said, ‘That would mean running a 4:03.’

“When he left, I told my mom, ‘That’s what professional runners do. That’s crazy.’ But he had that confidence in me and put that confidence in myself. I took that to heart.”

Last year, at the Oxy High Performance meet, Cain finished second in the 1500m in 4:04.62, breaking the American junior and youth records at the distance and achieving the World Championships A standard.

“Little did I know that I only needed to run 4:04,” Cain joked.

Later last summer, she finished second in 4:28.76 in a tactical race at the USA Outdoor Championships to qualify for Moscow. At Worlds, she clocked 4:08.21 in the opening round, 4:05.21 in the semifinals and finished 10th in the final in 4:07.19.

Those performances, Salazar believes, were just the beginning of Cain scratching the surface of her immense potential.

“She’s got a tremendous amount of talent and has run very fast at a young age,” he said. “She has a lot of raw, natural speed. It’s hard to predict where someone’s going to be but I expect she’s going to be someone that’s vying for more U.S. teams and she’s already a finalist at 17 at the World Championships. Improving just a little bit would put her in contention for medals, hopefully at some point.”

GOLD RUSH OUT WEST

It was around this time that the Cains began seriously considering the next step in their daughter’s progression.

Throughout their time working with Salazar, the family paid him for his coaching services as well as all the costs of her travel and running gear in order to preserve her NCAA eligibility.

But after concluding such an historic season, was running in college what was really best for Cain?

She ultimately decided that it wasn’t. Two days before receiving the Youth Athlete of the Year award and before Salazar received the Coach of the Year Award at the IAAF World Athletics Gala in Monaco last November, Cain announced that she was going pro, joining the Nike Oregon Project fulltime.

She ultimately decided that it wasn’t. Two days before receiving the Youth Athlete of the Year award and before Salazar received the Coach of the Year Award at the IAAF World Athletics Gala in Monaco last November, Cain announced that she was going pro, joining the Nike Oregon Project fulltime.

“When all of my friends started to get freaked out over college, I kind of got into that wave,” she admitted that day. “I was really only looking at a few schools and I kind of narrowed it down to one, which was U of O (Oregon). I had an amazing trip there, and the coaches are really nice people. They definitely made it really hard for me, and I thank them for that.

“Ultimately, I decided to go pro because that is what makes the most amount of sense for me. I know there are a lot of people saying, ‘By going pro she isn’t going to have as much fun and will miss the team stuff.’ My take is that I have had such an amazing year this year just based on the fun of it. I looked at both options, and both were great, but I kind of wanted to keep doing what I was doing and I felt the best way to do that was to take the next step by going pro.”

Cain continued working under Henwood’s watchful eye while finishing her senior year of high school. On the track, she was twice able to smash the world junior indoor record at 1000m, setting it at 2:35.80; improved her American junior record in the mile to 4:24.11, .01 off the world junior mark; and most recently captured gold in the 3000m in 8:58.48 at the World Junior Championships in Eugene.

“I think about how far I have come with Alberto all of the time, especially this summer,” Cain said. “I looked back on the last two years and could say, ‘Wow. It has only been two years and look at what has happened.’ Having that was a humbling experience, being able to look at it. It was nice being with all of the other juniors being excited and getting to say, ‘I did this in two years. You can do it too.’”

Cain and Salazar expect a lot more to come, now that she has enrolled at the University of Portland and can train with the Nike Oregon Project group in Beaverton full-time.

“I would say the biggest benefit is her training with the other top athletes,” Salazar said. “That’s where she will get a lot of her confidence, from running with Jordan (Hasay) and Treniere (Moser) and Shannon Rowbury. That’s going to get her to do stuff in workouts that having a guy pace her back here in New York is not the same thing. She is going to be able to do much better workouts.”

For her part, Cain said she feels more like a pro being out in Portland.

For her part, Cain said she feels more like a pro being out in Portland.

“The workouts are harder,” she said. “We have less recovery time. I can’t do the, ‘Oh-I-am-a-little-kid’ thing as much. I’m smacked around and told to do it. Another part of it was that I used to train on Bronxville’s track or at Van Cortlandt and there were a lot of people around and it was a different atmosphere. But here, you’re at Nike and it makes it that much more intense. The intensity makes it a different experience. I’m the type of person who loves it.”

When Cain moved onto campus in Portland earlier this month, her mom pulled her aside to check and make sure her daughter was indeed in a good place mentally.

“She asked me, ‘Are you happy?’” Cain said. “I told her, ‘I am literally living my dream.’

“Every day, I thank God that Alberto called me.”

Mary, a precocious middle-distance running talent for the local high school in Bronxville, was already tucked in bed at the time.

The caller ID registered an unrecognizable Oregon number. Fully anticipating it to be one of those annoying telemarketers, the call went unanswered and straight to the answering machine.

The voice on the other end of the line introduced himself.

“Hello, this is Alberto Salazar.”

Now two years removed from that fateful night and into an “amazing partnership,” that has already seen her reach the final of the 1500m in her first trip to the World Championships and win gold in the 3000m at the World Junior Championships, Cain wonders where she would be today had Salazar not reached out.

“It’s crazy looking back,” Cain admitted during a conversation in the lobby of the venerable 89th Street office of the New York Road Runners. “That week I was actually debating whether or not I should take a two-year leave of absence from the sport.

There was also ambitious goal setting from the outset.

There was also ambitious goal setting from the outset.“Then came a phone call which started off with Alberto being like, ‘I just want to give you some advice,’ to one that has turned me into a professional athlete living in Portland.”

TRIALS RUN IN

Cain actually had her first meeting with Salazar, now the esteemed coach of the Nike Oregon Project, earlier that summer at the 2012 U.S. Olympic Trials – as a wide-eyed, 15-year-old fan of the Cuban immigrant from Massachusetts who won three consecutive New York City Marathon titles from 190-82 and won the famed “Duel in the Sun” over Dick Beardsley at the 1982 Boston Marathon.

“I took a picture with him because he is Alberto Salazar,” Cain said. “It was actually pretty funny because I was so nervous going over to him and he was like, ‘Oh, are you that fast high school girl?’ And I was like ‘Yeah!’”

Salazar’s recollection of the moment is more matter-of-fact.

“She and her coach came by and the coach introduced us,” he said. “I had heard of her before and so we just chatted a little while.”

Added Cain: “Since then, I’ve asked him, ‘How did you know who I was?’ He goes, ‘You know, being an East Coast guy I always loved it when East Coast people would beat those California kids so you were kind of on my radar.’”

The two went their separate ways after that meeting, Salazar on to the London Olympics where he guided Britain’s Mo Farah to gold medals in the 5000m and 10,000m and American Galen Rupp to silver in the 10,000m, and Cain off to the World Junior Championships in Barcelona where she finished sixth in 4:11.01, breaking the American high school record.

The two went their separate ways after that meeting, Salazar on to the London Olympics where he guided Britain’s Mo Farah to gold medals in the 5000m and 10,000m and American Galen Rupp to silver in the 10,000m, and Cain off to the World Junior Championships in Barcelona where she finished sixth in 4:11.01, breaking the American high school record.When Salazar returned home from the Games, he pulled up a YouTube video of Cain’s race and was struck as much by her raw speed as her biomechanics, which featured a fluid stride but a chicken-wing arm swing – Cain says her arm motion was “absolutely awful” – due to lack of upper-body strength.

“I remember kind of seeing her form and how she was really running with her elbows out and stuff,” Salazar said, “so I called her coach to tell him to make sure that he worked on her form and that she could have a great career if they worked on her biomechanics. The coach that I was put through told me that he was no longer coaching her. I asked, ‘Well who is coaching her?’ He said we don’t know yet.”

So Salazar asked for Cain’s phone number.

CALLING PLACED ON HOLD

Cain returned home from Europe for the start of her junior year at Bronxville High, but while her peers were readying for the start of the cross-country season, she was a runner without a home.

She had parted ways with her high school coach, a situation she chooses not to delve into specifically, only saying that it “was not healthy and it had nothing to do with me or my family; it was just other outside influences that were making it difficult for me to continue.”

While Cain never lost her passion for running – “I told my parents, ‘I can’t not run. I have to. I can’t just leave it,’ she said – she was lost navigating the world of running. Without a coach directing her course, she wrote her own workouts but was clueless as to how or where she could race.

“I wouldn’t have known where to go on the local circuit,” Cain said. “I don’t even know what that means. I had absolutely no guidance. I was out there training myself, doing my own thing. I wanted to do local stuff but we didn’t know what to do. We were at a loss.”

The predicament seemed so hopeless that Cain gave serious consideration to giving up running for the remainder of her high school years.

“My parents and I were literally contemplating calling up college coaches, calling Oregon, Georgetown, Stanford, all of those places and saying, ‘Hey, I am going to stop running for two years,’” Cain admitted. “We were at the point of telling coaches, ‘I’ve run 4:11. I know I can run better. I can’t do it right now, but remember me in two years!’”

Salazar says that had Cain been forced to make that decision, she might not have been able to fully reach her potential.

“If she had decided to not run at all and then try to start again in college, it would have obviously been a huge step backward for her,” he explained. “She would have lost all of that conditioning and momentum she had going forward. Not that it would have been impossible to start up again but taking a two-year break is pretty tough.”

For her part, Cain isn’t sure what would have happened.

“Honestly there is a very good chance that Mary Cain wouldn’t have run at all her junior or senior years of high school,” she said. “I’d like to think that the college coaches would have called me two years later. There might be some excitement this weekend to see what I would be doing in cross country because you wouldn’t have seen me since that day I ran 4:11.”

THE RIGHT CALL

Desperate times call for desperate measures. Cain thought back to that day she met a running icon and got her picture taken with him at the Trials. Call it a dream or a prayer, but she wondered if Salazar would ever consider coaching someone like her.

“I joke with Alberto that at the time I was actually looking for his email to reach out and say, ‘Hey, I know you’re super-cool and I’m just a random kid, but if you could even just give me some advice, I would be forever grateful,’” Cain said. “I literally told my mom the week before that I was going to do that. I said, ‘He seems like such a nice guy. I’m sure he would at least email me back.’

“I joke with Alberto that at the time I was actually looking for his email to reach out and say, ‘Hey, I know you’re super-cool and I’m just a random kid, but if you could even just give me some advice, I would be forever grateful,’” Cain said. “I literally told my mom the week before that I was going to do that. I said, ‘He seems like such a nice guy. I’m sure he would at least email me back.’ “And then he called me.”

Upon hearing the name “Alberto Salazar,” come through the answering machine, Cain’s mother, also named Mary, leapt to her feet and dove for the phone like she was lunging across an Olympic finish line.

“I did the 100-yard dash in two seconds,” she told espnW last April.

“The only thing I heard was my mom bolt for the phone,” Cain said, adding that the noise startled her for a moment, but did not fully wake her.

“I ended up calling (Cain’s) parents and said whoever is coaching her, or if you can find some club coach, have them work on her mechanics,” Salazar said. “Her mom asked me if I knew of any coaches out there and I said that I didn’t really know but that she could ask around and maybe there were some club coaches.

“She asked if I would be willing to give her some workouts at least temporarily to get her through the cross-country season, and I said ‘Okay, yeah. Fine. I can do that.’”

Two hours later, Cain was woken by her parents and let in on the conversation.

“When he actually called, I can’t tell you the level of excitement,” Cain’s father, Charlie, told The New York Times in 2012. “Mary was very excited. It was quite literally an answer to a prayer.”

“My mom still jokes about this, but when we got the call from Alberto she was the most excited because she was like, ‘I watched your marathons! I know who you are!’” Cain said. “And of course we watched the London Olympics. I was actually at the beach when the 10-K was going off. Nobody else in my family runs besides me, and they were all there sitting and watching it. I come home five minutes later and was like, ‘You didn’t call me?’ So I had to watch it myself online.”

A few days after Salazar’s initial phone call, Cain spoke to him on the phone and the two “just really clicked pretty instantly.”

"The first time we sat down he said, 'This is a 10-year program. I don't want you peaking at age 16,'" Cain told espnW last year.

Salazar added: "Mary knows what I told her; she has as much talent as any young athlete I've ever seen in running -- in my life."

After those initially conversations, Cain began getting direction from Salazar. It didn’t take long for word to spread that the two were working together.

“When everybody found out about it, it was probably two or three weeks after we had first met,” Cain said. “There were a lot of people saying, ‘Oh, you were meeting secretly in the summer.’ That was all me coaching myself. I was doing my little random workouts there. They were pretty good. I was proud of those. But finally he was like, ‘Okay, we’re going to start giving you workouts and building up to it.’”

When the Cains realized they had found the perfect coach for their daughter, they proceeded quickly, but not star-struck.

“We were all big fans of Alberto, but the big thing with my parents was that they wanted to make sure that it worked,” she said. “They didn’t want me to get into a super-intense program that is crazy that early. Alberto is the best coach in the world. When we sat down and talked to him, we also realized that he is the nicest guy in the world, and is really there for his athletes. He pours 110 percent into each of us. It was like, how could I say no? We had no real reservations.”

STARTING SLOWLY

Salazar, however, did give pause.

“I started telling her a few workouts to do and she did pretty well,” he said. “We kept talking a couple of times a week, and they asked me if I was willing to continue doing that. I had to think about that carefully. Just the responsibility of getting involved with a 16- or 17-year-old girl living across the country, and whether I had the time to put forth the commitment to do it. But then I said, ‘What the heck.’ It had gone pretty well for the first month so why not.”

Because Cain did not want to move to a boarding school in Oregon, Salazar needed to find a coach-in-residence, so to speak. He enlisted the help of John Henwood, a 2004 Olympian for New Zealand who works as a coach and massage therapist in Manhattan, to supervise her daily workouts.

“John Henwood has done a fantastic job,” Salazar said. “I feel like Mary has been well-monitored while she’s here.”

“Alberto and I sat down in person when he was in town for an appearance,” Cain recalled. “He said his goal was for me to make the 2013 Worlds team and I actually kind of laughed in his face. I said, ‘That would mean running a 4:03.’

“When he left, I told my mom, ‘That’s what professional runners do. That’s crazy.’ But he had that confidence in me and put that confidence in myself. I took that to heart.”

Last year, at the Oxy High Performance meet, Cain finished second in the 1500m in 4:04.62, breaking the American junior and youth records at the distance and achieving the World Championships A standard.

“Little did I know that I only needed to run 4:04,” Cain joked.

Later last summer, she finished second in 4:28.76 in a tactical race at the USA Outdoor Championships to qualify for Moscow. At Worlds, she clocked 4:08.21 in the opening round, 4:05.21 in the semifinals and finished 10th in the final in 4:07.19.

Those performances, Salazar believes, were just the beginning of Cain scratching the surface of her immense potential.

“She’s got a tremendous amount of talent and has run very fast at a young age,” he said. “She has a lot of raw, natural speed. It’s hard to predict where someone’s going to be but I expect she’s going to be someone that’s vying for more U.S. teams and she’s already a finalist at 17 at the World Championships. Improving just a little bit would put her in contention for medals, hopefully at some point.”

GOLD RUSH OUT WEST

It was around this time that the Cains began seriously considering the next step in their daughter’s progression.

Throughout their time working with Salazar, the family paid him for his coaching services as well as all the costs of her travel and running gear in order to preserve her NCAA eligibility.

But after concluding such an historic season, was running in college what was really best for Cain?

She ultimately decided that it wasn’t. Two days before receiving the Youth Athlete of the Year award and before Salazar received the Coach of the Year Award at the IAAF World Athletics Gala in Monaco last November, Cain announced that she was going pro, joining the Nike Oregon Project fulltime.

She ultimately decided that it wasn’t. Two days before receiving the Youth Athlete of the Year award and before Salazar received the Coach of the Year Award at the IAAF World Athletics Gala in Monaco last November, Cain announced that she was going pro, joining the Nike Oregon Project fulltime.“When all of my friends started to get freaked out over college, I kind of got into that wave,” she admitted that day. “I was really only looking at a few schools and I kind of narrowed it down to one, which was U of O (Oregon). I had an amazing trip there, and the coaches are really nice people. They definitely made it really hard for me, and I thank them for that.

“Ultimately, I decided to go pro because that is what makes the most amount of sense for me. I know there are a lot of people saying, ‘By going pro she isn’t going to have as much fun and will miss the team stuff.’ My take is that I have had such an amazing year this year just based on the fun of it. I looked at both options, and both were great, but I kind of wanted to keep doing what I was doing and I felt the best way to do that was to take the next step by going pro.”

Cain continued working under Henwood’s watchful eye while finishing her senior year of high school. On the track, she was twice able to smash the world junior indoor record at 1000m, setting it at 2:35.80; improved her American junior record in the mile to 4:24.11, .01 off the world junior mark; and most recently captured gold in the 3000m in 8:58.48 at the World Junior Championships in Eugene.

“I think about how far I have come with Alberto all of the time, especially this summer,” Cain said. “I looked back on the last two years and could say, ‘Wow. It has only been two years and look at what has happened.’ Having that was a humbling experience, being able to look at it. It was nice being with all of the other juniors being excited and getting to say, ‘I did this in two years. You can do it too.’”

Cain and Salazar expect a lot more to come, now that she has enrolled at the University of Portland and can train with the Nike Oregon Project group in Beaverton full-time.

“I would say the biggest benefit is her training with the other top athletes,” Salazar said. “That’s where she will get a lot of her confidence, from running with Jordan (Hasay) and Treniere (Moser) and Shannon Rowbury. That’s going to get her to do stuff in workouts that having a guy pace her back here in New York is not the same thing. She is going to be able to do much better workouts.”

For her part, Cain said she feels more like a pro being out in Portland.

For her part, Cain said she feels more like a pro being out in Portland.“The workouts are harder,” she said. “We have less recovery time. I can’t do the, ‘Oh-I-am-a-little-kid’ thing as much. I’m smacked around and told to do it. Another part of it was that I used to train on Bronxville’s track or at Van Cortlandt and there were a lot of people around and it was a different atmosphere. But here, you’re at Nike and it makes it that much more intense. The intensity makes it a different experience. I’m the type of person who loves it.”

When Cain moved onto campus in Portland earlier this month, her mom pulled her aside to check and make sure her daughter was indeed in a good place mentally.

“She asked me, ‘Are you happy?’” Cain said. “I told her, ‘I am literally living my dream.’

“Every day, I thank God that Alberto called me.”