New York City Marathon 2014Oct 31, 2014 by Joe Battaglia

Coe, Radcliffe Key To Ridding Athletics Of Doping

Coe, Radcliffe Key To Ridding Athletics Of Doping

NEW YORK –– As Claudio Berardelli walked into the media room at the Javits Center, the coach looked like a man who hadn’t slept a wink the night before.

Which is understandable considering his prized runner, Rita Jeptoo, was outed overnight by RunBlogRun.com as having failed an out-of-competition doping test.

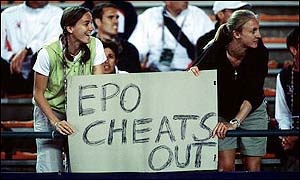

The AFP reported today that the substance the 33-year-old winner of back-to-back Boston and Chicago Marathons tested positive for in her A sample was EPO. Her B sample has yet to be tested.

Jeptoo, who was due to arrive here to claim the World Marathon Majors title and accompanying $500,000 this weekend, instead remains in Kenya “confused” while the sport reels once again from a doping scandal, this time on the eve of the world’s biggest road race, the TCS New York City Marathon.

“I believe these guys have huge talent there and I am sure that 99 percent of my athletes are clean,” said Berardelli, who has in recent years seen two of his other athletes, Matthew Kisorio and Jumima Sungong fail doping tests. Sumgong, who escaped punishment on a technicality, will race here on Sunday

“I talk to them on a daily basis about this doping issue and now, to say the truth, I am still a little bit shocked about this news. I feel stupid. I feel like I’m no longer able to do this job — I don’t know what is my real impact because now it seems like there is something going on behind the scenes. I am not an expert on this, but I would say that there is probably something going on from within Kenya, something local.”

Which has been the speculation for years.

Between 2010 and 2012 only two athletes were suspended for performance-enhancing drug violations. That number increased to 17 between January 2012 and last October as the World Anti-Doping Agency heightened its focus on the country amid frustration with procrastination by Athletics Kenya.

"Compared to other countries we do not have a serious problem,” AK president Isaiah Kiplagat told the BBC last year.

Stop the denials Mr. Kiplagat. Kenya does have a doping problem.

But more disturbingly, in 2014, so does the sport of marathoning. The World Marathon Majors has endured the disgrace of having two-time series champion Liliya Shobukhova of Russia test positive and narrowly avoided having a third crowned-champion in Jeptoo be stripped of her title.

We’re talking $1.5 million in WMM prize money, not to mention untold prize money and appearance fees paid by Chicago Marathon race director Carey Pinkowski only to see five of his last six winners popped for doping, and shoe-company bonuses.

The current measures being employed by WADA, including frequent blood testing, biological passports and mandatory four-year bans – like the one Jeptoo is facing – are steps in the right direction.

However, this sport needs to take gargantuan leaps forward if dopers are to be driven out completely and some measure of credibility is to be restored.

“A lot of what you see you can’t believe it and some other things you see raise questions,” marathon world record holder Paula Radcliffe said. “That’s why the bottom line is that we need to improve the testing so people can believe what they are watching. Otherwise it makes the whole thing a lottery.”

Added Berardelli: “This could definitely destroy the system, even for those who are clean. I think the credibility of the entire Kenyan system will be affected. People will say, ‘Now we know why they are running fast.’”

Make no mistake, these are dark times for the sport. To pull out of it, two things need to happen.

Firstly, Sebastian Coe needs to be elected president of the IAAF next year, succeeding Lamine Diack, who quite frankly has held this office too long. There is no one in athletics leadership more staunchly opposed to doping than Coe.

When asked about the Jeptoo situation on his 2019 World Championships evaluation trip to Doha, Coe declined comment. However, his remarks to the BBC last November make his position on the subject pretty clear.

“If you asked me if we could have a non-negotiable stance on this, is this a war we can afford to lose, the answer is that it isn’t,” Coe said. “Trust and integrity are really important and trust and integrity are not just concepts rooted on the field of play. We have to make sure that we have federations and organizations that are structured to be able to deal with the issue of confidence, whether it’s the spectators going to a stadium knowing what they are watching has integrity behind it, whether it’s the athletes knowing that the athletes on either side of them are going to be in the exact same system that they are.”

Coe as president would certainly bring the structure that he speaks of to the IAAF. He could send a serious message by appointing Radcliffe to be his anti-doping czar.

An outspoken critic of dopers during the prime of her racing career, the 40-year-old said she is now prepared to “put her effort where her mouth is” now that she has reached the twilight of her time as an elite marathoner.

“I have obviously backed Sebastian Coe to get in as president and then I would be really interested in going into the (IAAF) anti-doping department,” Radcliffe said. “It is something I would consider at this point in my career because it is something that I feel passionate about. That whole department needs to be comprised of people that feel passionate about it. It is happening but it needs to happen more and more.”

Radcliffe said the biggest change needed would be to drive significantly more resources at anti-doping measures.

“I would invest triple, quadruple the budget and make sure the labs were all over the world so that the proper blood passporting can be carried out everywhere, out of competition testing can be carried out everywhere, and a little more targeted testing where you are going off rumors,” she said. “Make it known that cheaters are not welcome in our sport, are not good for our sport, and are not going to be tolerated. Someone needs to stand up for the clean athletes who go into race after race and are getting beaten by people who are cheating.

“There isn’t enough invested in anti-doping at the moment,” Radcliffe continued. “Generally, for our sport, it is time for a change. That is not a huge criticism of (Lamine Diack) but Seb is someone who can change that and can move our sport forward. It needs modernizing.”

Radcliffe acknowledged that the doping problem in marathoning is not isolated to Kenya and she does not advocate “a witch hunt” in the country, but she said socioeconomic realities have left East Africa open to doping becoming prevalent if left unchecked.

“The difference that winning a race like New York or London or Boston or Chicago can make to a runner in East Africa is huge so obviously the motivation to take a shortcut is huge too,” she said. “It’s not such a stigma and you haven’t got as much to lose as a U.S. athlete or a European athlete if you get caught. The evidence that is coming out is that it’s not that difficult to get your hands on EPO. When people say these people have nothing or no means to access anything like that they obviously do because the cases have happened.

“There have been rumors for a long time that proper testing has not been carried out in all of East Africa and a lot of other areas. They should want to have that testing in place there because there are a lot of athletes who work and train hard there. They want to be able to prove that they are clean as well. The IAAF has a responsibility to put that testing in place.”

Weary from the situation, Berardelli offered up this poignant statement.

“If the story of Rita can be the key to open the door to ending the dirty system, then please let Rita pay for it,” he said.

While doping once again casts its shadow over one of the biggest events in the sport, if it is what ultimately ushers Coe and Radcliffe in as the IAAF’s new anti-doping tag team, then it’s a small price to pay in the long run.

Which is understandable considering his prized runner, Rita Jeptoo, was outed overnight by RunBlogRun.com as having failed an out-of-competition doping test.

The AFP reported today that the substance the 33-year-old winner of back-to-back Boston and Chicago Marathons tested positive for in her A sample was EPO. Her B sample has yet to be tested.

Jeptoo, who was due to arrive here to claim the World Marathon Majors title and accompanying $500,000 this weekend, instead remains in Kenya “confused” while the sport reels once again from a doping scandal, this time on the eve of the world’s biggest road race, the TCS New York City Marathon.

“I believe these guys have huge talent there and I am sure that 99 percent of my athletes are clean,” said Berardelli, who has in recent years seen two of his other athletes, Matthew Kisorio and Jumima Sungong fail doping tests. Sumgong, who escaped punishment on a technicality, will race here on Sunday

“I talk to them on a daily basis about this doping issue and now, to say the truth, I am still a little bit shocked about this news. I feel stupid. I feel like I’m no longer able to do this job — I don’t know what is my real impact because now it seems like there is something going on behind the scenes. I am not an expert on this, but I would say that there is probably something going on from within Kenya, something local.”

Which has been the speculation for years.

Between 2010 and 2012 only two athletes were suspended for performance-enhancing drug violations. That number increased to 17 between January 2012 and last October as the World Anti-Doping Agency heightened its focus on the country amid frustration with procrastination by Athletics Kenya.

"Compared to other countries we do not have a serious problem,” AK president Isaiah Kiplagat told the BBC last year.

Stop the denials Mr. Kiplagat. Kenya does have a doping problem.

But more disturbingly, in 2014, so does the sport of marathoning. The World Marathon Majors has endured the disgrace of having two-time series champion Liliya Shobukhova of Russia test positive and narrowly avoided having a third crowned-champion in Jeptoo be stripped of her title.

We’re talking $1.5 million in WMM prize money, not to mention untold prize money and appearance fees paid by Chicago Marathon race director Carey Pinkowski only to see five of his last six winners popped for doping, and shoe-company bonuses.

The current measures being employed by WADA, including frequent blood testing, biological passports and mandatory four-year bans – like the one Jeptoo is facing – are steps in the right direction.

However, this sport needs to take gargantuan leaps forward if dopers are to be driven out completely and some measure of credibility is to be restored.

“A lot of what you see you can’t believe it and some other things you see raise questions,” marathon world record holder Paula Radcliffe said. “That’s why the bottom line is that we need to improve the testing so people can believe what they are watching. Otherwise it makes the whole thing a lottery.”

Added Berardelli: “This could definitely destroy the system, even for those who are clean. I think the credibility of the entire Kenyan system will be affected. People will say, ‘Now we know why they are running fast.’”

Make no mistake, these are dark times for the sport. To pull out of it, two things need to happen.

Firstly, Sebastian Coe needs to be elected president of the IAAF next year, succeeding Lamine Diack, who quite frankly has held this office too long. There is no one in athletics leadership more staunchly opposed to doping than Coe.

When asked about the Jeptoo situation on his 2019 World Championships evaluation trip to Doha, Coe declined comment. However, his remarks to the BBC last November make his position on the subject pretty clear.

“If you asked me if we could have a non-negotiable stance on this, is this a war we can afford to lose, the answer is that it isn’t,” Coe said. “Trust and integrity are really important and trust and integrity are not just concepts rooted on the field of play. We have to make sure that we have federations and organizations that are structured to be able to deal with the issue of confidence, whether it’s the spectators going to a stadium knowing what they are watching has integrity behind it, whether it’s the athletes knowing that the athletes on either side of them are going to be in the exact same system that they are.”

Coe as president would certainly bring the structure that he speaks of to the IAAF. He could send a serious message by appointing Radcliffe to be his anti-doping czar.

An outspoken critic of dopers during the prime of her racing career, the 40-year-old said she is now prepared to “put her effort where her mouth is” now that she has reached the twilight of her time as an elite marathoner.

“I have obviously backed Sebastian Coe to get in as president and then I would be really interested in going into the (IAAF) anti-doping department,” Radcliffe said. “It is something I would consider at this point in my career because it is something that I feel passionate about. That whole department needs to be comprised of people that feel passionate about it. It is happening but it needs to happen more and more.”

Radcliffe said the biggest change needed would be to drive significantly more resources at anti-doping measures.

“I would invest triple, quadruple the budget and make sure the labs were all over the world so that the proper blood passporting can be carried out everywhere, out of competition testing can be carried out everywhere, and a little more targeted testing where you are going off rumors,” she said. “Make it known that cheaters are not welcome in our sport, are not good for our sport, and are not going to be tolerated. Someone needs to stand up for the clean athletes who go into race after race and are getting beaten by people who are cheating.

“There isn’t enough invested in anti-doping at the moment,” Radcliffe continued. “Generally, for our sport, it is time for a change. That is not a huge criticism of (Lamine Diack) but Seb is someone who can change that and can move our sport forward. It needs modernizing.”

Radcliffe acknowledged that the doping problem in marathoning is not isolated to Kenya and she does not advocate “a witch hunt” in the country, but she said socioeconomic realities have left East Africa open to doping becoming prevalent if left unchecked.

“The difference that winning a race like New York or London or Boston or Chicago can make to a runner in East Africa is huge so obviously the motivation to take a shortcut is huge too,” she said. “It’s not such a stigma and you haven’t got as much to lose as a U.S. athlete or a European athlete if you get caught. The evidence that is coming out is that it’s not that difficult to get your hands on EPO. When people say these people have nothing or no means to access anything like that they obviously do because the cases have happened.

“There have been rumors for a long time that proper testing has not been carried out in all of East Africa and a lot of other areas. They should want to have that testing in place there because there are a lot of athletes who work and train hard there. They want to be able to prove that they are clean as well. The IAAF has a responsibility to put that testing in place.”

Weary from the situation, Berardelli offered up this poignant statement.

“If the story of Rita can be the key to open the door to ending the dirty system, then please let Rita pay for it,” he said.

While doping once again casts its shadow over one of the biggest events in the sport, if it is what ultimately ushers Coe and Radcliffe in as the IAAF’s new anti-doping tag team, then it’s a small price to pay in the long run.