USATF Outdoor ChampionshipsJun 25, 2015 by Joe Battaglia

Three Years After Heel Surgery, Erin Donohue Looks To Regain Footing At USAs

Three Years After Heel Surgery, Erin Donohue Looks To Regain Footing At USAs

As she swung her legs out of bed and put her feet down on the floor, Erin Donohue was struck by the soreness in her left heel. Aches and pains were not that

As she swung her legs out of bed and put her feet down on the floor, Erin Donohue was struck by the soreness in her left heel.

Aches and pains were not that uncommon in 2010. At age 28 and after about 15 years of training mileage and high-level competition, it was bound to happen. Besides, it would always loosen up and never kept her from running 80 to 100 miles per week. And to boot, she was in the midst of her best season as a pro.

But that all began to change around September that year, when relief became harder to find and workouts started to be adversely impacted.

“In the fall of 2010 it kept getting worse and worse,” Donohue said. “I would try to give it a couple days, ice it, get massaged, get active relief therapy. All the tricks that I knew and nothing made it better.”

Having never been seriously injured in her career, save a stress fracture that shortened one of her basketball seasons at Haddonfield High School, Donohue sought answers.

“My biggest thing was that I strained my calf a couple times, but nothing severe,” Donohue said. “Other than that I never had plantar fasciitis, the IT band stuff, none of that.“

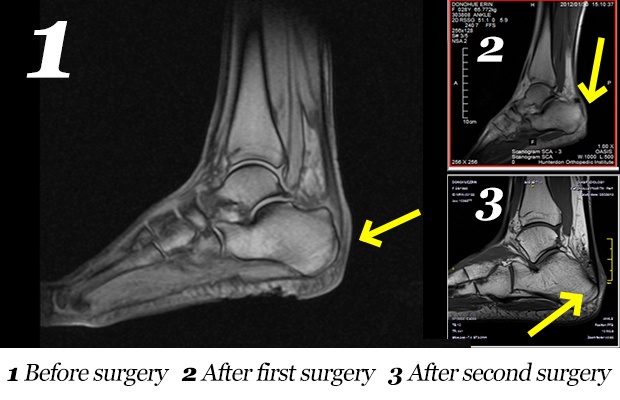

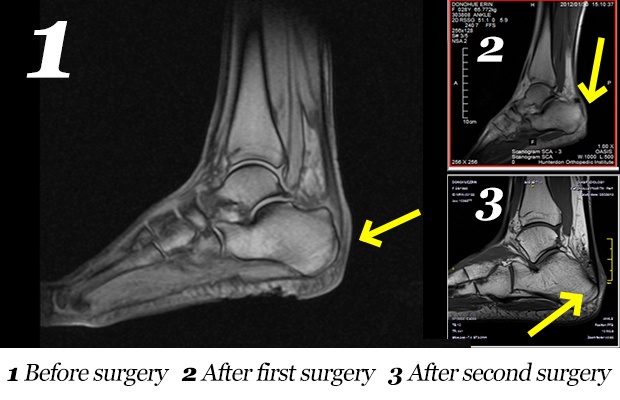

The initial diagnosis was bursitis, but shockwave therapy turned out to be a fruitless treatment. It wasn’t until undergoing an MRI in the spring of 2011 that Donohue learned that the root cause of her pain was a bone deformity in her left heel and that surgery was likely the course of action that would get her back on the track and racing at the top of her game.

That was two surgeries and four years of recovery ago, a relative eternity in this sport. Over that time, Donohue became a forgotten entity in elite American middle distance running.

That is until June 13, when the 2008 Olympian toed the start line at the Diamond League adidas Grand Prix in New York and won the 1000m in 2:37.42, taking down a field that included the likes of Mary Cain and Treniere Moser of the Nike Oregon Project and 2011 Worlds silver medalist Olympian Hannah England of Great Britain.

Donohue’s reemergence plan will take her to Eugene this week where she will compete in the women’s 800m at the USA Outdoor Championships, ostensibly to vie for a spot on the Worlds team headed to Beijing but also to reclaim lost years.

“I want to go out there and I want to win, but I don’t feel pressure,” Donohue said. “I’m happy to be here. I appreciate just having the opportunity to compete there and I’m just going to go and make the most of every round.”

Coming off the 2010 season, Donohue’s expectations were sky high. She had made the transition from coach John Cook to Frank Gagliano at the New Jersey*New York Track Club and was starting to see results that her new training was taking hold.

That year, she ran PRs indoors in the 800m (2:03.77), the 1000m (2:38.98), the 1500m (4:09.59) and the mile (4:38.12), outdoors in the 800m (1:59.99) and the 1500m (4:03.49), and on the roads in the mile (4:24.40) and the 5K (15:50).

“I felt great. I felt strong. Everything was going in the right direction,” Donohue said. “I was working with Gags and he works closely with Jim Radcliffe out at Oregon, so I had a really good sort of strength training kind of component to everything. I was really looking forward to 2011 and you know rolling right into 2012. It never really crossed my mind that a sudden drop-off could happen.

“If you look at the trajectory of my career, I never made any huge leaps in PRs or anything, but almost every year since high school I've PRed a little bit in the mile and the 800m and I just kept cranking down, cranking down, cranking down. I just assumed I would just keep going in that direction. So to fall off a cliff like that was very disappointing.”

The pain from bursitis in her heel began impacting training for the first time in her career in 2011. Suddenly she was unable to consistently string together solid workouts like she had her entire life.

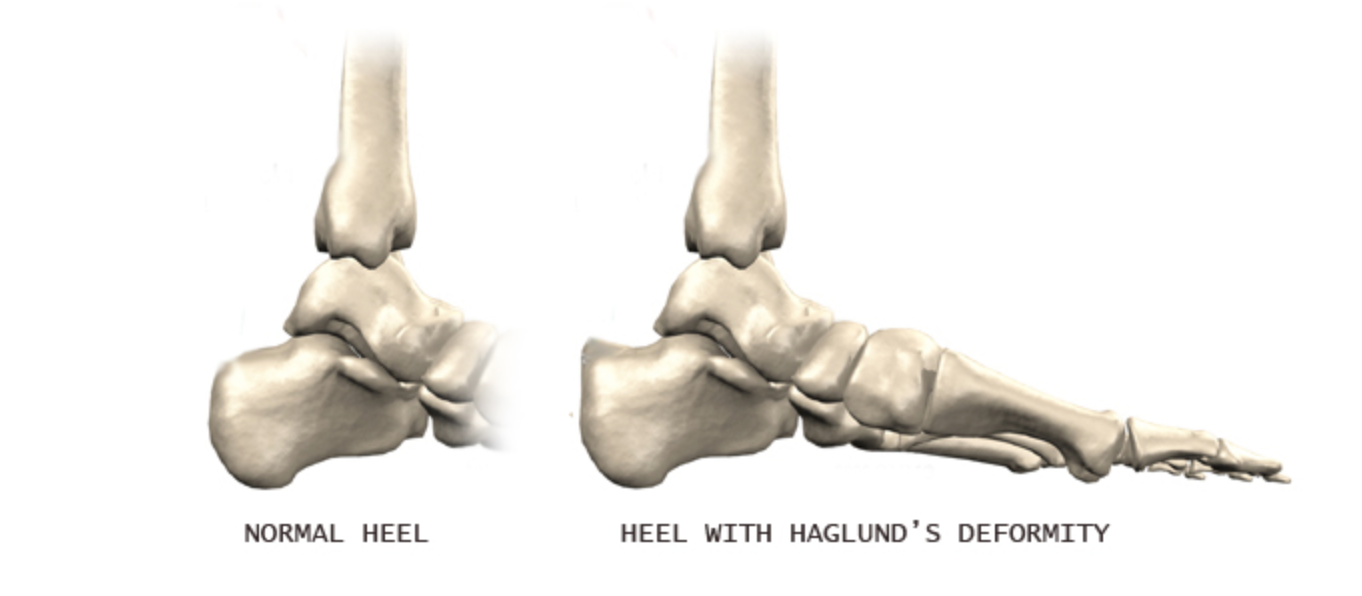

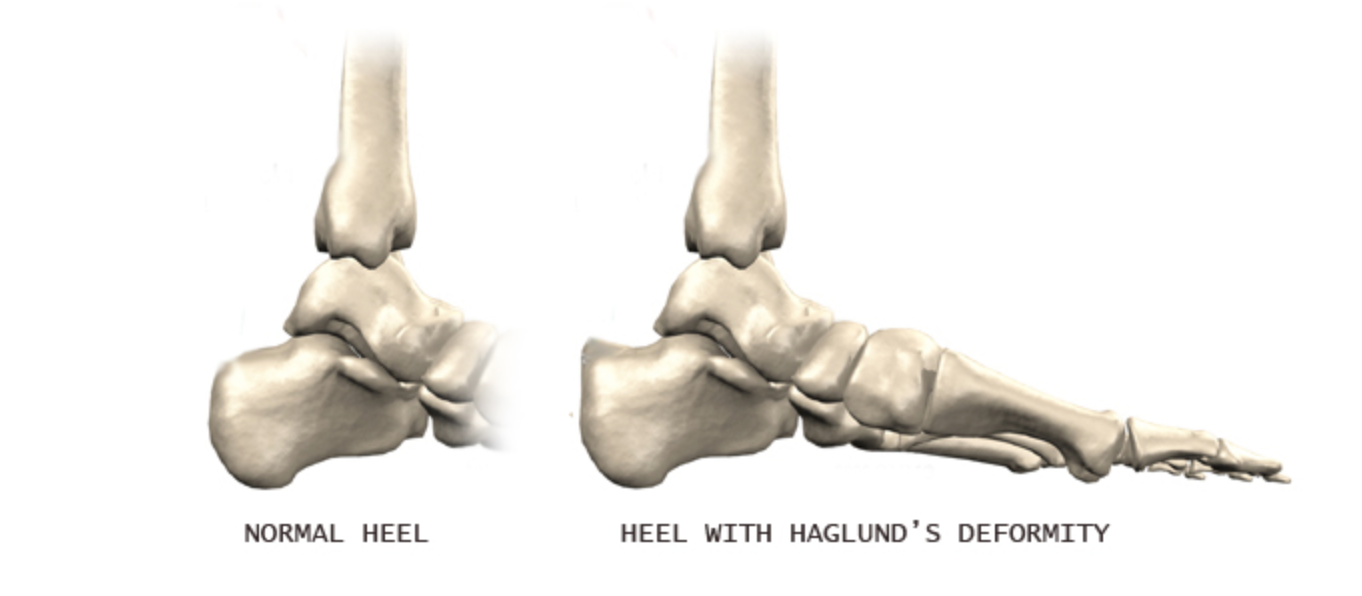

That spring, she was finally diagnosed with Haglund’s Syndrome, a deformity that arises when the bony section of one’s heel, where the Achilles tendon is located, becomes enlarged. The bursitis Donohue was initially diagnosed with was an inflammation of the fluid-filled sac that separates the tendon from the bone. When the heel became inflamed, it led to the calcification of her heel bone, causing the “pump bump” to become even more prominent and painful.

“I kind of made a deal with this one doctor to just let me compete this season, see if I can make the Worlds Team and run through the season,” Donohue said. “I told him, ‘Give me a cortisone shot and then I'll get the surgery at the end of the summer.’”

On top of that, Donohue pulled out all of the customary tricks from the Runner’s Bag Of Quick Fixes --- she cut the back of the heel off her racing flats, tried a hard heel cup and a heel counter – to continue competing, but her performances fell short of expectations. She was unable to make the team that competed in Daegu and wound up running 2:02.40 for 800m, 4:07.04 for 1500m and 8:55.07 for 3000m.

“I ran okay, but it wasn’t as good as I was wanting because my training was just inconsistent and I was always dealing with the soreness and just a lot of pain in my heel and up through my calf,” Donohue said.

After the season, she opted to have surgery. According to Donohue, Drs. Mark Myerson and Rebecca Cerrato at the Institute for Foot and Ankle Reconstruction at Mercy Hospital in Baltimore opted for a less-invasive endoscopic procedure and gave her a recovery timeline of four to six weeks.

With the 2012 Olympic year just around the corner, that was music to her ears.

With the 2012 Olympic year just around the corner, that was music to her ears.

“When they sell you on a surgery, orthopedic surgeons are the most confident people in the world about that surgery,” Donohue said. “When I heard that four-to-six week timeline and we go in, we snip a little here, bada bing, bada boom, you do a little physical therapy, you stretch out, then everything’s good. I really believed that.

“You watch SportsCenter and you hear about guys in the NFL having all kind of surgeries and they’re back in that timeline, four-to-six weeks. Without knowing anything about surgery, I just assumed that you could really trust it. It’s good 100 percent of the time, and, you know, I'm an athlete anyway so I'm going to recover really fast and it’s going to be great, it’s going to be easy. I actually went into that first surgery extremely confident.”

Donohue’s surgery was performed without complications and she said she “honestly thought I’d be back fully training by November.” She spent just three weeks in a walking boot and was never put in a full cast. But when November turned into December, December into January, genuine worry set in for the first time.

“The swelling never went down properly,” Donohue explained. “Honestly, even the stitches didn’t seem to be healing properly. You could just tell that the bone, a lot of it was still there.”

At that point, Donohue sought a second opinion on her heel. Upon examination, Dr. Martin O’Malley at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York discovered that the initial surgery failed to remove enough of the calcified bone in Donohue’s left heel and that she would need a second surgery and lengthier recovery period to correct the issue.

“It was difficult to figure out exactly how my foot would react,” Donohue said. “I knew going in that the typical recovery time for this second surgery and the way they went in with a larger incision and a larger tool, was going to be eight-to-12 weeks.

“It was difficult to figure out exactly how my foot would react,” Donohue said. “I knew going in that the typical recovery time for this second surgery and the way they went in with a larger incision and a larger tool, was going to be eight-to-12 weeks.

“I talked to a couple of other people who had the surgery. A friend of mine, Megan Kaltenbach, who ran North Carolina, had the surgery and she said eight-to-12 weeks was about right and she was up running and playing tennis and doing all normal activities again at 12 weeks.”

Left a bit jaded by the results of her first surgery, Donohue said she, “almost forced Dr. O’Malley to do an x-ray right away to show me that the extra bone is gone.” Indeed, the calcification was completely removed. However, the second surgery took longer than three months to heal, a product of essentially having two major procedures done on the same area in less than a year’s time.

This time, Donohue spent two weeks after surgery in a hard cast and was in a boot and on crutches for another six weeks after that. Once she began physical therapy, she hit the bike an elliptical machine, “harder than most people would,” and perhaps did, “a little too much too soon.”

“The area was very sensitive and it was really beat up from having a couple surgeries,” she said. “The trauma of cutting into a bone does cause a lot of swelling and a lot of scar tissue and everything. So it took more than eight-to-12 weeks before everything was even just started to calm down, even though I was going to physical therapy, trying to do all the right things.

“One of the problems I ran into was going back and straining my calf and irritating things just because the range of motion was limited. My left side was weaker than my right side and it basically, it just took a lot of time to gain back all the strength and range of motion that I really needed to train.

“I think I may have been better off staying longer in the cast or, I don’t know, if you gave me a wheelchair and strapped me into it so I couldn’t do anything for a long time.”

At that point, Donohue gave up any hope of recovering in time to compete at the 2012 Olympic Trials. She also knew her inability to compete during the year when track and field receives the most attention put her Nike sponsorship, her livelihood, and her future in the sport in jeopardy.

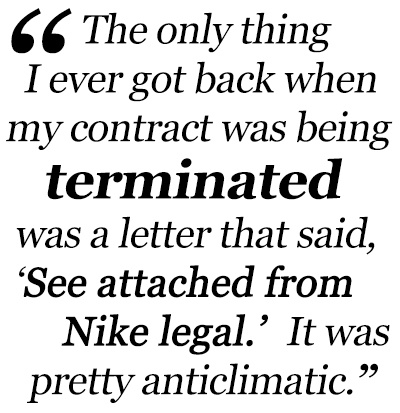

“I wrote a letter to John Capriotti (Nike’s Global Director of Athletics) and Ben Cesar (Nike’s Athlete Marketing Manager) just explaining my circumstance,” Donohue said. “I knew my contract had already been reduced because I didn’t run in 2011 and I was pretty sure when it was up in 2012 it wasn’t going to be renewed. I knew I was going to lose sponsorship because if you can’t run, then you're pretty much useless to them.

“But I wrote them a letter and just explained that I wasn’t just blowing off track and going on vacation somewhere, I had had this surgery. I never heard anything back from them. The only thing I ever got back was when my contract was being terminated a letter that said, ‘See attached from Nike legal.’ That was it. It was pretty anticlimactic.”

While Donohue lost her sponsorship, her training situation with the New Jersey*New York Track Club remained stable.

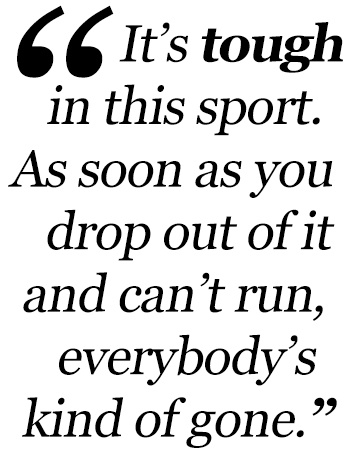

“On the positive side, I never lost touch with Gags and so I always had at least continuity of a coach who always knew where I was at and was always working with me,” Donohue said. “It’s tough in this sport. By 2012, I'd been running professionally for seven, almost eight years. And you think you might have some kind of relationship with Nike, some kind of relationship with other people in sport. But as soon as you drop out of it and can’t run, everybody’s kind of gone. So it was extremely important to have Gags there too to just keep my foot in the world of track and field just a little bit because then otherwise I would have been just totally out of it.”

When Donohue was healed enough to try running again in the fall of 2012, she was hit with immediate physical limitations. Any run longer than 15 to 25 minutes would result in a buildup of swelling in her left heel and the onset of pain and stiffness.

It was then that she discovered that her typical approach to training – volume to build endurance before moving to more explosive workouts to develop speed – would have to be done in reverse. For the first time in her life, she would attempt to come at middle-distance running from the speed end.

“Where I kind of made an adjustment is I figured out after a while that for whatever reason doing sprints and doing explosive weightlifting did not bother my foot as much as the long, slow distance kind of stuff,” Donohue said. “At some point around the end of 2012 and into 2013, I started training with work on the things I need to work on anyway, just in a different order.”

“Where I kind of made an adjustment is I figured out after a while that for whatever reason doing sprints and doing explosive weightlifting did not bother my foot as much as the long, slow distance kind of stuff,” Donohue said. “At some point around the end of 2012 and into 2013, I started training with work on the things I need to work on anyway, just in a different order.”

Donohue’s cross-training regimen included swimming at the Jersey Wahoos Swim Club in Mount Laurel, N.J. – “I don’t know how swimmers just stare down at the bottom of the pool for hour after hour,” she said – and would do hard intervals biking around the neighborhood before fear of being hit by a car scared her into purchasing a good stationary trainer for home.

For a time, Donohue did her weightlifting at a local gym. Since slamming bars was frowned upon there, she eventually needed to find somewhere else to powerlift. Before building her own weight room in the basement of her house in Haddon Heights, Donohue used her key as a middle school track coach to sneak into the weight room at Haddonfield High, her alma mater. It was a cathartic experience.

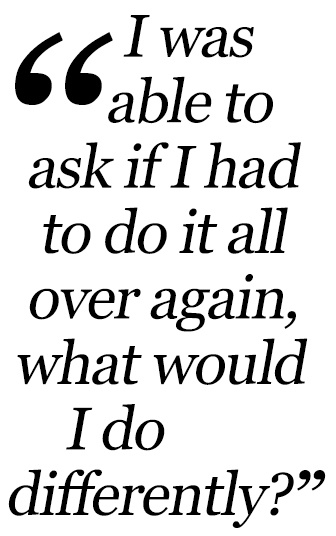

“I had this time to kind of look back and reflect on everything in my career,” she said. “I was able to ask if I had to do it all over again, what would I do differently? I really went back and looked at my training logs and looked at some of my past races and knew I needed to work on range of motion and I needed to work on strength and becoming more efficient.

“I had this time to kind of look back and reflect on everything in my career,” she said. “I was able to ask if I had to do it all over again, what would I do differently? I really went back and looked at my training logs and looked at some of my past races and knew I needed to work on range of motion and I needed to work on strength and becoming more efficient.

“I would have definitely spent more time working on my flexibility because that’s something I kind of always blew off and now that I can feel my hamstrings are looser and my hips are looser, running suddenly became a lot easier. Aerobically I might not be where I was before my injury, but I'm hitting all my workouts in the same times or better times because my hips are looser and I can just, I don’t have to fight myself as much coming down the track anymore.”

Those track workouts remained problematic for some time. Donohue resumed running during the late summer in 2013, but even light 200s that felt good immediately afterward would leave her calves feeling sore and tight and her heel swollen.

“I couldn’t put workouts together with any kind of consistency,” Donohue said. “So I just had to wait. I guess the first time I put them together with some consistency was really the winter of 2014 and then into the spring I really started to put in a few good weeks and months of training together before I blew out my calf a little bit in May.”

Because she was so fit, Donohue was able to resume training fairly quickly after that setback. On July 26, she returned to competition for the first time in three years, joining New Jersey*New York Track Club teammates Cydney Ross, Stephanie Charnigo and Latavia Thomas for a 4x800m relay at the Run TrackTown High Performance Meet in Eugene. The team finished third in 8:14.76.

“I was like an old lady running against these 22-year-olds that probably never heard of me before,” Donohue said. “It was just kind of funny to come back and see a whole new set of faces. I just remember being really relaxed and just kind of happy to be there and really excited to be there. I really had a good time with that. It was just really a great experience and kind of low-key meet for me to get my toe back into the track and field waters, so to speak.”

By this point, Donohue knew she had reached two significant milestones. Physically, she was not only able to string together workouts on the track but also to race hard again. Psychologically, she could do all of the above without “thinking about my foot, my injury, or contingency plans with every step.”

Regaining racing confidence has been a work in progress. In May, Donohue jumped in an open 800m race at Westchester Henderson High School in Pennsylvania and ran 2:07, losing to Sarah Walker, a touted junior at Germantown Friends.

Regaining racing confidence has been a work in progress. In May, Donohue jumped in an open 800m race at Westchester Henderson High School in Pennsylvania and ran 2:07, losing to Sarah Walker, a touted junior at Germantown Friends.

“The pace went out slow and it was kind of a funky race,” Donohue recalled. “I tried not to get discouraged that I just got beat by a 16 year old, and then I moved on. My next race after that was the Hoka One One meet at Occidental and I ran 2:04.18 there. Then I ran an open 800m at Ridge High School and went 2:02.”

Donohue’s biggest breakthrough came at the adidas Grand Prix, winning a tough race against a quality professional field on a big stage.

“I knew my workouts were good, but no one was expecting anything of me,” she said. “I was expecting to compete well but I didn’t really feel any outside pressure to do anything because everybody's looking at Mary Cain and Treniere Moser and Hannah England in the race. All around, I couldn’t really lose because I knew I was in good shape and all I had to do was go out there and compete. If I won, that’d be great. If I didn’t win, nobody would know the difference anyway.”

The Next Chapter

While she might get a bit more notice from the knowledgeable Hayward Field crowd, Donohue knows she will be heading to the USA Outdoor Championships as a major underdog. But her confidence hasn’t diminished any.

“I know I’m very confident in myself and I know I can go out there and get through the rounds,” she said. “But I am very realistic in that I’m probably facing the best group of 800-meter runners of any country in the world right now. You have seven or eight girls who are more than capable of running under two minutes. You have three or four of them who are capable of running 1:57.

“I just have to go out there and be confident enough to put myself in a position to advance through the rounds, stay loose, stay relaxed, and just trust in my training. Just comparing my workouts and knowing where I’m at, I do think under the right circumstances I could definitely get under two and break my PR.”

Donohue has loftier goals for the future, including an eventual return to racing the 1500m, the event she qualified for the Beijing Olympics in in 2008. How she performs in the 800m at USAs will ultimately determine how soon that will happen. Regardless, her aim is to be back in serious contention for a national team spot come next summer’s Olympic Trials.

Donohue has loftier goals for the future, including an eventual return to racing the 1500m, the event she qualified for the Beijing Olympics in in 2008. How she performs in the 800m at USAs will ultimately determine how soon that will happen. Regardless, her aim is to be back in serious contention for a national team spot come next summer’s Olympic Trials.

That she can even think of this in realistic terms is a tribute to Donohue’s determination and will to succeed. At age 32 and with her body broken, her financial support lost, and her place in the sort murky at best, she could have – and some might say should have – walked away fulfilled and begun the next chapter in her life.

But that simply is not Donohue.

“No doctor ever tells you it’s going to take three or four years to get back,” she said. “If someone told me at the end of 2010 into 2011, ‘Hey, you’re not going to be running really well again until 2015,’ I think that would probably have changed my mind and I might have just stopped at that point. But I just kept going along four to six weeks at a time and just kind of figured that, ‘I’m in the heat of this now, now I’ve got to keep going.’ It’s a combination of that and the fact that I really do enjoy running and competing.

“So, that’s why I’m still here and I’m still just about young enough to hang in there and do it.”

Aches and pains were not that uncommon in 2010. At age 28 and after about 15 years of training mileage and high-level competition, it was bound to happen. Besides, it would always loosen up and never kept her from running 80 to 100 miles per week. And to boot, she was in the midst of her best season as a pro.

But that all began to change around September that year, when relief became harder to find and workouts started to be adversely impacted.

“In the fall of 2010 it kept getting worse and worse,” Donohue said. “I would try to give it a couple days, ice it, get massaged, get active relief therapy. All the tricks that I knew and nothing made it better.”

Having never been seriously injured in her career, save a stress fracture that shortened one of her basketball seasons at Haddonfield High School, Donohue sought answers.

“My biggest thing was that I strained my calf a couple times, but nothing severe,” Donohue said. “Other than that I never had plantar fasciitis, the IT band stuff, none of that.“

The initial diagnosis was bursitis, but shockwave therapy turned out to be a fruitless treatment. It wasn’t until undergoing an MRI in the spring of 2011 that Donohue learned that the root cause of her pain was a bone deformity in her left heel and that surgery was likely the course of action that would get her back on the track and racing at the top of her game.

That was two surgeries and four years of recovery ago, a relative eternity in this sport. Over that time, Donohue became a forgotten entity in elite American middle distance running.

That is until June 13, when the 2008 Olympian toed the start line at the Diamond League adidas Grand Prix in New York and won the 1000m in 2:37.42, taking down a field that included the likes of Mary Cain and Treniere Moser of the Nike Oregon Project and 2011 Worlds silver medalist Olympian Hannah England of Great Britain.

Donohue’s reemergence plan will take her to Eugene this week where she will compete in the women’s 800m at the USA Outdoor Championships, ostensibly to vie for a spot on the Worlds team headed to Beijing but also to reclaim lost years.

“I want to go out there and I want to win, but I don’t feel pressure,” Donohue said. “I’m happy to be here. I appreciate just having the opportunity to compete there and I’m just going to go and make the most of every round.”

The Heel Wouldn’t Heal

Coming off the 2010 season, Donohue’s expectations were sky high. She had made the transition from coach John Cook to Frank Gagliano at the New Jersey*New York Track Club and was starting to see results that her new training was taking hold.

That year, she ran PRs indoors in the 800m (2:03.77), the 1000m (2:38.98), the 1500m (4:09.59) and the mile (4:38.12), outdoors in the 800m (1:59.99) and the 1500m (4:03.49), and on the roads in the mile (4:24.40) and the 5K (15:50).

“I felt great. I felt strong. Everything was going in the right direction,” Donohue said. “I was working with Gags and he works closely with Jim Radcliffe out at Oregon, so I had a really good sort of strength training kind of component to everything. I was really looking forward to 2011 and you know rolling right into 2012. It never really crossed my mind that a sudden drop-off could happen.

“If you look at the trajectory of my career, I never made any huge leaps in PRs or anything, but almost every year since high school I've PRed a little bit in the mile and the 800m and I just kept cranking down, cranking down, cranking down. I just assumed I would just keep going in that direction. So to fall off a cliff like that was very disappointing.”

The pain from bursitis in her heel began impacting training for the first time in her career in 2011. Suddenly she was unable to consistently string together solid workouts like she had her entire life.

That spring, she was finally diagnosed with Haglund’s Syndrome, a deformity that arises when the bony section of one’s heel, where the Achilles tendon is located, becomes enlarged. The bursitis Donohue was initially diagnosed with was an inflammation of the fluid-filled sac that separates the tendon from the bone. When the heel became inflamed, it led to the calcification of her heel bone, causing the “pump bump” to become even more prominent and painful.

“I kind of made a deal with this one doctor to just let me compete this season, see if I can make the Worlds Team and run through the season,” Donohue said. “I told him, ‘Give me a cortisone shot and then I'll get the surgery at the end of the summer.’”

On top of that, Donohue pulled out all of the customary tricks from the Runner’s Bag Of Quick Fixes --- she cut the back of the heel off her racing flats, tried a hard heel cup and a heel counter – to continue competing, but her performances fell short of expectations. She was unable to make the team that competed in Daegu and wound up running 2:02.40 for 800m, 4:07.04 for 1500m and 8:55.07 for 3000m.

“I ran okay, but it wasn’t as good as I was wanting because my training was just inconsistent and I was always dealing with the soreness and just a lot of pain in my heel and up through my calf,” Donohue said.

Surgical Imprecision

After the season, she opted to have surgery. According to Donohue, Drs. Mark Myerson and Rebecca Cerrato at the Institute for Foot and Ankle Reconstruction at Mercy Hospital in Baltimore opted for a less-invasive endoscopic procedure and gave her a recovery timeline of four to six weeks.

With the 2012 Olympic year just around the corner, that was music to her ears.

With the 2012 Olympic year just around the corner, that was music to her ears.“When they sell you on a surgery, orthopedic surgeons are the most confident people in the world about that surgery,” Donohue said. “When I heard that four-to-six week timeline and we go in, we snip a little here, bada bing, bada boom, you do a little physical therapy, you stretch out, then everything’s good. I really believed that.

“You watch SportsCenter and you hear about guys in the NFL having all kind of surgeries and they’re back in that timeline, four-to-six weeks. Without knowing anything about surgery, I just assumed that you could really trust it. It’s good 100 percent of the time, and, you know, I'm an athlete anyway so I'm going to recover really fast and it’s going to be great, it’s going to be easy. I actually went into that first surgery extremely confident.”

Donohue’s surgery was performed without complications and she said she “honestly thought I’d be back fully training by November.” She spent just three weeks in a walking boot and was never put in a full cast. But when November turned into December, December into January, genuine worry set in for the first time.

“The swelling never went down properly,” Donohue explained. “Honestly, even the stitches didn’t seem to be healing properly. You could just tell that the bone, a lot of it was still there.”

At that point, Donohue sought a second opinion on her heel. Upon examination, Dr. Martin O’Malley at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York discovered that the initial surgery failed to remove enough of the calcified bone in Donohue’s left heel and that she would need a second surgery and lengthier recovery period to correct the issue.

“It was difficult to figure out exactly how my foot would react,” Donohue said. “I knew going in that the typical recovery time for this second surgery and the way they went in with a larger incision and a larger tool, was going to be eight-to-12 weeks.

“It was difficult to figure out exactly how my foot would react,” Donohue said. “I knew going in that the typical recovery time for this second surgery and the way they went in with a larger incision and a larger tool, was going to be eight-to-12 weeks.“I talked to a couple of other people who had the surgery. A friend of mine, Megan Kaltenbach, who ran North Carolina, had the surgery and she said eight-to-12 weeks was about right and she was up running and playing tennis and doing all normal activities again at 12 weeks.”

Cut…Again

Left a bit jaded by the results of her first surgery, Donohue said she, “almost forced Dr. O’Malley to do an x-ray right away to show me that the extra bone is gone.” Indeed, the calcification was completely removed. However, the second surgery took longer than three months to heal, a product of essentially having two major procedures done on the same area in less than a year’s time.

This time, Donohue spent two weeks after surgery in a hard cast and was in a boot and on crutches for another six weeks after that. Once she began physical therapy, she hit the bike an elliptical machine, “harder than most people would,” and perhaps did, “a little too much too soon.”

“The area was very sensitive and it was really beat up from having a couple surgeries,” she said. “The trauma of cutting into a bone does cause a lot of swelling and a lot of scar tissue and everything. So it took more than eight-to-12 weeks before everything was even just started to calm down, even though I was going to physical therapy, trying to do all the right things.

“One of the problems I ran into was going back and straining my calf and irritating things just because the range of motion was limited. My left side was weaker than my right side and it basically, it just took a lot of time to gain back all the strength and range of motion that I really needed to train.

“I think I may have been better off staying longer in the cast or, I don’t know, if you gave me a wheelchair and strapped me into it so I couldn’t do anything for a long time.”

At that point, Donohue gave up any hope of recovering in time to compete at the 2012 Olympic Trials. She also knew her inability to compete during the year when track and field receives the most attention put her Nike sponsorship, her livelihood, and her future in the sport in jeopardy.

“I wrote a letter to John Capriotti (Nike’s Global Director of Athletics) and Ben Cesar (Nike’s Athlete Marketing Manager) just explaining my circumstance,” Donohue said. “I knew my contract had already been reduced because I didn’t run in 2011 and I was pretty sure when it was up in 2012 it wasn’t going to be renewed. I knew I was going to lose sponsorship because if you can’t run, then you're pretty much useless to them.

“But I wrote them a letter and just explained that I wasn’t just blowing off track and going on vacation somewhere, I had had this surgery. I never heard anything back from them. The only thing I ever got back was when my contract was being terminated a letter that said, ‘See attached from Nike legal.’ That was it. It was pretty anticlimactic.”

Glimmers Of Hope

While Donohue lost her sponsorship, her training situation with the New Jersey*New York Track Club remained stable.

“On the positive side, I never lost touch with Gags and so I always had at least continuity of a coach who always knew where I was at and was always working with me,” Donohue said. “It’s tough in this sport. By 2012, I'd been running professionally for seven, almost eight years. And you think you might have some kind of relationship with Nike, some kind of relationship with other people in sport. But as soon as you drop out of it and can’t run, everybody’s kind of gone. So it was extremely important to have Gags there too to just keep my foot in the world of track and field just a little bit because then otherwise I would have been just totally out of it.”

When Donohue was healed enough to try running again in the fall of 2012, she was hit with immediate physical limitations. Any run longer than 15 to 25 minutes would result in a buildup of swelling in her left heel and the onset of pain and stiffness.

It was then that she discovered that her typical approach to training – volume to build endurance before moving to more explosive workouts to develop speed – would have to be done in reverse. For the first time in her life, she would attempt to come at middle-distance running from the speed end.

“Where I kind of made an adjustment is I figured out after a while that for whatever reason doing sprints and doing explosive weightlifting did not bother my foot as much as the long, slow distance kind of stuff,” Donohue said. “At some point around the end of 2012 and into 2013, I started training with work on the things I need to work on anyway, just in a different order.”

“Where I kind of made an adjustment is I figured out after a while that for whatever reason doing sprints and doing explosive weightlifting did not bother my foot as much as the long, slow distance kind of stuff,” Donohue said. “At some point around the end of 2012 and into 2013, I started training with work on the things I need to work on anyway, just in a different order.”Donohue’s cross-training regimen included swimming at the Jersey Wahoos Swim Club in Mount Laurel, N.J. – “I don’t know how swimmers just stare down at the bottom of the pool for hour after hour,” she said – and would do hard intervals biking around the neighborhood before fear of being hit by a car scared her into purchasing a good stationary trainer for home.

For a time, Donohue did her weightlifting at a local gym. Since slamming bars was frowned upon there, she eventually needed to find somewhere else to powerlift. Before building her own weight room in the basement of her house in Haddon Heights, Donohue used her key as a middle school track coach to sneak into the weight room at Haddonfield High, her alma mater. It was a cathartic experience.

“I had this time to kind of look back and reflect on everything in my career,” she said. “I was able to ask if I had to do it all over again, what would I do differently? I really went back and looked at my training logs and looked at some of my past races and knew I needed to work on range of motion and I needed to work on strength and becoming more efficient.

“I had this time to kind of look back and reflect on everything in my career,” she said. “I was able to ask if I had to do it all over again, what would I do differently? I really went back and looked at my training logs and looked at some of my past races and knew I needed to work on range of motion and I needed to work on strength and becoming more efficient.“I would have definitely spent more time working on my flexibility because that’s something I kind of always blew off and now that I can feel my hamstrings are looser and my hips are looser, running suddenly became a lot easier. Aerobically I might not be where I was before my injury, but I'm hitting all my workouts in the same times or better times because my hips are looser and I can just, I don’t have to fight myself as much coming down the track anymore.”

Those track workouts remained problematic for some time. Donohue resumed running during the late summer in 2013, but even light 200s that felt good immediately afterward would leave her calves feeling sore and tight and her heel swollen.

“I couldn’t put workouts together with any kind of consistency,” Donohue said. “So I just had to wait. I guess the first time I put them together with some consistency was really the winter of 2014 and then into the spring I really started to put in a few good weeks and months of training together before I blew out my calf a little bit in May.”

Back On Track

Because she was so fit, Donohue was able to resume training fairly quickly after that setback. On July 26, she returned to competition for the first time in three years, joining New Jersey*New York Track Club teammates Cydney Ross, Stephanie Charnigo and Latavia Thomas for a 4x800m relay at the Run TrackTown High Performance Meet in Eugene. The team finished third in 8:14.76.

“I was like an old lady running against these 22-year-olds that probably never heard of me before,” Donohue said. “It was just kind of funny to come back and see a whole new set of faces. I just remember being really relaxed and just kind of happy to be there and really excited to be there. I really had a good time with that. It was just really a great experience and kind of low-key meet for me to get my toe back into the track and field waters, so to speak.”

By this point, Donohue knew she had reached two significant milestones. Physically, she was not only able to string together workouts on the track but also to race hard again. Psychologically, she could do all of the above without “thinking about my foot, my injury, or contingency plans with every step.”

“The pace went out slow and it was kind of a funky race,” Donohue recalled. “I tried not to get discouraged that I just got beat by a 16 year old, and then I moved on. My next race after that was the Hoka One One meet at Occidental and I ran 2:04.18 there. Then I ran an open 800m at Ridge High School and went 2:02.”

Donohue’s biggest breakthrough came at the adidas Grand Prix, winning a tough race against a quality professional field on a big stage.

“I knew my workouts were good, but no one was expecting anything of me,” she said. “I was expecting to compete well but I didn’t really feel any outside pressure to do anything because everybody's looking at Mary Cain and Treniere Moser and Hannah England in the race. All around, I couldn’t really lose because I knew I was in good shape and all I had to do was go out there and compete. If I won, that’d be great. If I didn’t win, nobody would know the difference anyway.”

The Next Chapter

While she might get a bit more notice from the knowledgeable Hayward Field crowd, Donohue knows she will be heading to the USA Outdoor Championships as a major underdog. But her confidence hasn’t diminished any.

“I know I’m very confident in myself and I know I can go out there and get through the rounds,” she said. “But I am very realistic in that I’m probably facing the best group of 800-meter runners of any country in the world right now. You have seven or eight girls who are more than capable of running under two minutes. You have three or four of them who are capable of running 1:57.

“I just have to go out there and be confident enough to put myself in a position to advance through the rounds, stay loose, stay relaxed, and just trust in my training. Just comparing my workouts and knowing where I’m at, I do think under the right circumstances I could definitely get under two and break my PR.”

Donohue has loftier goals for the future, including an eventual return to racing the 1500m, the event she qualified for the Beijing Olympics in in 2008. How she performs in the 800m at USAs will ultimately determine how soon that will happen. Regardless, her aim is to be back in serious contention for a national team spot come next summer’s Olympic Trials.

Donohue has loftier goals for the future, including an eventual return to racing the 1500m, the event she qualified for the Beijing Olympics in in 2008. How she performs in the 800m at USAs will ultimately determine how soon that will happen. Regardless, her aim is to be back in serious contention for a national team spot come next summer’s Olympic Trials.That she can even think of this in realistic terms is a tribute to Donohue’s determination and will to succeed. At age 32 and with her body broken, her financial support lost, and her place in the sort murky at best, she could have – and some might say should have – walked away fulfilled and begun the next chapter in her life.

But that simply is not Donohue.

“No doctor ever tells you it’s going to take three or four years to get back,” she said. “If someone told me at the end of 2010 into 2011, ‘Hey, you’re not going to be running really well again until 2015,’ I think that would probably have changed my mind and I might have just stopped at that point. But I just kept going along four to six weeks at a time and just kind of figured that, ‘I’m in the heat of this now, now I’ve got to keep going.’ It’s a combination of that and the fact that I really do enjoy running and competing.

“So, that’s why I’m still here and I’m still just about young enough to hang in there and do it.”