What if Suzy Favor-Hamilton Had Won Her Olympic Gold?

What if Suzy Favor-Hamilton Had Won Her Olympic Gold?

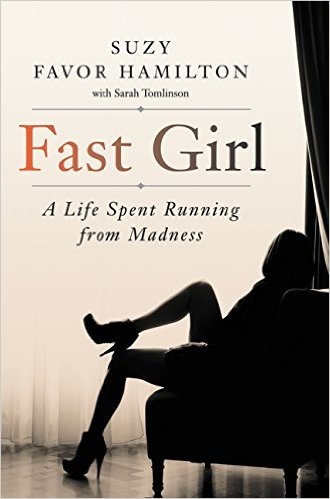

New memoir, “Fast Girl,” chronicles the nine-time NCAA champion and three-time Olympian’s fall from grace. But what about the other fall?

By Johanna Gretschel (@jojo_shea)

By Johanna Gretschel (@jojo_shea)

Nearly three years after The Smoking Gun outed Suzy Favor-Hamilton for her secret double life as a Las Vegas escort, the nine-time NCAA champion and three-time Olympian published her side of the story in a memoir released last week.

In “Fast Girl,” Favor-Hamilton describes with no details barred (and help from ghost writer Sarah Tomlinson) coming of age in the 1970s within a rocky family atmosphere in Wisconsin, her ascent to the top of American middle distance running and how she traded her spikes for lingerie in her second career as the No. 2 rated escort in Las Vegas while her husband cooperatively covered her tracks and raised their daughter back home in Wisconsin.

Despite her titles and athletic fame, Favor-Hamilton writes that no “runner’s high” compared to the feeling of prostitution.

“I was shaking, still riding the rush,” she writes.

“I was on fire. I was a winner… This is way better than winning a race, I thought. This is better than competing in the Olympics. If only my friends, all my fellow runners, could feel what this is like, they’d get it. Why are they still running races? If I’d only known how amazing this felt, I never would have wasted all that time.”

“I was on fire. I was a winner… This is way better than winning a race, I thought. This is better than competing in the Olympics. If only my friends, all my fellow runners, could feel what this is like, they’d get it. Why are they still running races? If I’d only known how amazing this felt, I never would have wasted all that time.”

Favor-Hamilton was eventually diagnosed with bipolar disorder, the same mental illness that caused her brother to take his own life the year before the Atlanta Games.

Before the diagnosis, she took Zoloft to manage her postpartum depression - a medication that intensifies the manic symptoms of bipolar. Manic individuals typically engage in thrill-seeking and dangerous behaviors, including gambling, drug and alcohol use, unprotected sex, shoplifting, and really, any act - lawful or unlawful - that produces a high.

For Favor Hamilton, that mania manifested itself in hyper sexuality, which she dealt with by first paying for escort services, then picking up strangers in bars and then finally becoming an escort herself and deriving her high from interacting with clients and accepting their luxurious gifts.

She immediately found the escort lifestyle more thrilling than winning any race, or appearing in any Olympic final.

The tone of book shifts when she and Mark, her husband (to whom she is still married), make their first trip to Vegas together to rekindle a wavering flame on their 20th wedding anniversary. They hire “Pearl,” a female escort, for a threesome.

To that point, Favor-Hamilton’s depiction of her competitive racing career and post-track family life is resoundingly negative.

When she meets Pearl, everything changes.

“I’d found happiness in Vegas,” she writes, “which had finally taken me out of anxiety and sadness.”

The story churns onward from there, through scandalous details and shopping sprees and finally, the confrontation with the Smoking Gun reporter as Mark is preparing to purchase a condo in Las Vegas so Suzy can cut down on hotel expenses.

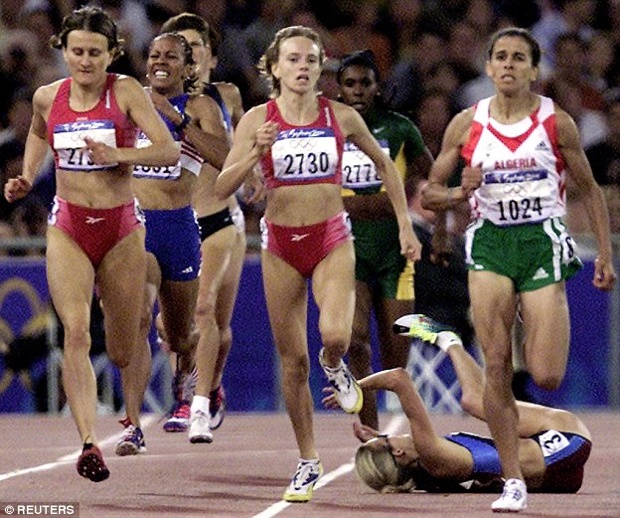

For how many scandalous details it reveals, the text raises even more questions - and not even about the sex, but the state of college athletics and mental health of elite athletes. The most interesting part of Suzy, for me as a runner, is still “the fall” - not this Smoking Gun fall from grace, but the “other” one. Her literal, deliberate fall in the 1500m final at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games upon realizing she is no longer in medal contention.

The 32-year-old Favor-Hamilton entered that race with the fastest time in the world that year: 3:57.4.

U.S. Olympic Trials champion Regina Jacobs had withdrawn from the Games with a respiratory viral infection.

Defending Olympic champion Svetlana Masterkova of Russia did not make it through the first round.

Favor-Hamilton advanced safely through the rounds and took the lead in the final with 800 meters to go. With 150 meters remaining, it was still Suzy’s blonde ponytail that led the pack.

But for once, her overzealous competitive drive is overpowered by a paralyzing anxiety.

“…the closer I got to the finish line the more certain I became that something terrible was going to happen, any second…I tried to hold on, but the tornado of negative thoughts and doubts was spinning through my brain faster and faster. My legs grew heavier and heavier, and with 150 meters left, one by one, the other runners passed me, until there was no one left but me. I was going to come in last in my last Olympic race… Heartbroken, panicked, almost dumb with grief, I just stopped. I told myself to fall, and then, I fell.”

What made Suzy become the woman she is today and what affect did that final Olympic race have on the rest of her life?

Suzy and Mark don’t meet Pearl until more than 100 pages into the book. To that point, readers gain a fair amount of insight into the world of an elite distance runner and the University of Wisconsin athletic department in the late 1980s.

The following are a few revealing passages into that world where I dog-eared the page:

Eating disorders were common at the University of Wisconsin, though Suzy seems to think that perhaps the trend has changed.

“Peter recruited the most driven runners he could find, runners who, like me, were willing to do absolutely anything to be the best, and many of the girls he trained over the years developed eating disorders. I don’t think that there is a direct link, or blame to be placed. The 1980s were a different time in sports, and we were much less sophisticated in our knowledge of nutrition and how it could impact performance… We were also teenage girls, having our first experience away from home. We didn’t think about balancing what was on our plates. We’d eat an entire bag of cookies, or whatever was salty, fatty, or sweet, and then do what we had to do to get rid of the excess in our bodies.” (p.42)

University of Wisconsin coaches sexually harassed Suzy

“…one of the coaches of the men’s track team had filmed me while I was training and showed his team members a video of my breasts bouncing as I ran.” (p. 44)

No one cared how Suzy performed in school - or if she took exams at all

“When I entered the University of Wisconsin, my academic advisor was well aware of how poor my grades had been in high school and how difficult it had been for me to get into college, even with my obvious running talent… my particularly low scores on the English portion [of college entry exams] revealed that I most likely had a learning disability. I had such a myopic focus on my running that I didn’t take the time to really absorb what this might mean, and no one I encountered in the school’s administration or athletics department ever addressed my academic prospects: they simply wanted me to keep winning.” (p.44-45)

In a later scene, Favor describes returning to school for a psychology final the day after placing runner-up at the NCAA XC Championship. At the urging of a teammate, she simply tells her professor that she did not study for the exam. The professor tells her she does not need to take it. He averages her prior test grades (C, D) to giver her a final grade of C for the semester.

“I had a tutor who wrote a couple of my papers for me. I was not her only client, though, and she once wrote the exact same paper for twenty-five student athletes. This incident almost got me expelled, but I knew deep down that I would never get kicked out of school. I was too valuable a runner for the school to make that move.” (p. 46)

“Sitting in a classroom was torture for me, and I hated anything I wasn’t good at, so I didn’t even try. As far as I was concerned, I was already good at something - so why bother with the rest?” (p. 47)

Suzy tried to commit suicide in college

“…I got word that Mark was about to start dating someone else… I felt like my world was ending. I was in pain, and the pain had to end. I went into the bathroom, took a razor and cut my wrists.” (p. 57)

Suzy paid $8,000 for a breast reduction surgery after the 1992 Barcelona Games

“When I’d appeared on the cover of Runner’s World the previous year, they’d severely airbrushed my photo, decreasing my bust size so I appeared flat chested, the way female runners were supposed to look. I hated that my breasts still drew attention to me and made me look anything other than the absolute ideal runner. That summer, I secretly paid eight thousand dollars for breast reduction surgery, even though the doctors warned me I might have trouble breast-feeding if I ever became a mother.” (p.74)

Suzy thought about using PEDs

“I wondered if I was being naive about using drugs. I’d always vowed to run clean, but maybe that was a mistake.” (p. 78)

After she fails to medal in the 800m at the 1996 Atlanta Games, Favor asks her coach, Dick Brown, if she should experiment with performance-enhancing drugs.

“You are absolutely not going to do drugs,’ he said. ‘You don’t need them. You’re talented enough.’ I was relieved. I didn’t want to break the rules. I was a good girl. But, still, I wondered what I needed to do to win.” (p.79)

She later describes attending a party to celebrate after running her first sub-4 minute 1500m (incorrectly identified in the book as a “mile under four minutes”), a feat that garners her a $100,000 bonus from Nike.

She speaks with an unidentified “meet promoter for one of the most prestigious meets in the world” who implies that she cannot win gold without using PEDs.

“I was shocked and offended by what he’d just said without saying it: in order to be the best, I had to use steroids. If I did, I could change a sport I loved dearly. If I didn’t, it was my fault if I lost.” (p. 83)

Do you have to be a little bit crazy to run fast?

“Sure, I wanted to win. I liked to win. But, in truth, I needed to win. Even as I stood with my teammates, receiving my medal, the wheels in my head were turning. Now I have to win every state meet I ever run. There’s no choice. If I were to lose, I’d let everyone down - my parents, my coach, my community - and that can’t happen.

And thus began a cruel cycle in my life. The more obsessed I became, the faster I ran; the faster I ran, the more notoriety I received; and the more notoriety I received, the more obsessed I became. Soon, even winning wasn’t enough.” (p.26)

“My coach didn’t understand. No one could. I knew that I was in constant danger of failing at any moment. I knew that I was never good enough.” (p.27)

——

Would things be different for Suzy if she had never fallen in the Olympic final and achieved that ultimate high of an Olympic gold medal? The world will never know, but that question - and that unflagging, unhealthy, laser-focus competitive drive that made Suzy the winningest female athlete in Big 10 history is still the most fascinating part of her story.